My great grandfather John Gibbs was the coal and ice man in Perth Amboy New Jersey. That meant owning a truck and carting coal through the community in the winter so people could heat their homes. In the summer it meant driving huge blocks of ice through the community so people could fill their ice-boxes and keep their food from spoiling. When my grandfather, Jeremiah Gumbs, born on this day in 1913, married my grandmother Lydia Gibbs, he joined the family business. He told me about the time a huge block of ice slid off the truck and how in his haste to impress his father-in-law he jumped off the truck and picked up an unmanagably huge piece of ice (he says it weighed at least half a ton) with the force of sheer adrenaline. When my grandfather took over the business he updated it to become a heating and air-conditioning business beyond the time of coal and ice. He was able to afford to upgrade by going, in his army uniform, to a new base and getting the contract to heat and cool their facilities, and then with that contract in place, and with my grandmother supposedly sounding white on the phone, he got the loans to actually get the equipment he needed to fulfill that contract and also to upgrade heating and air-conditioning services in their own community of Caribbean migrants in Perth Amboy.

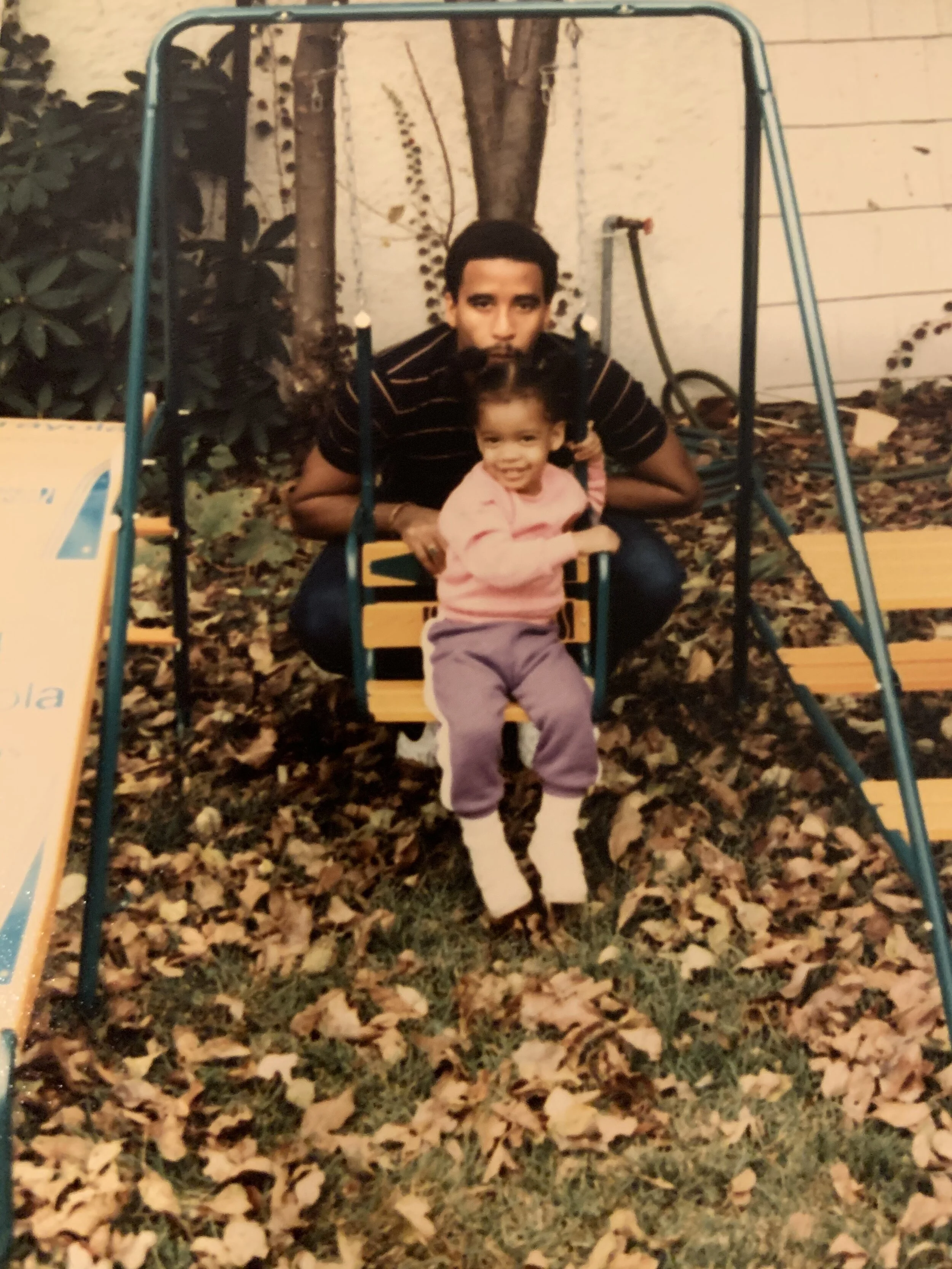

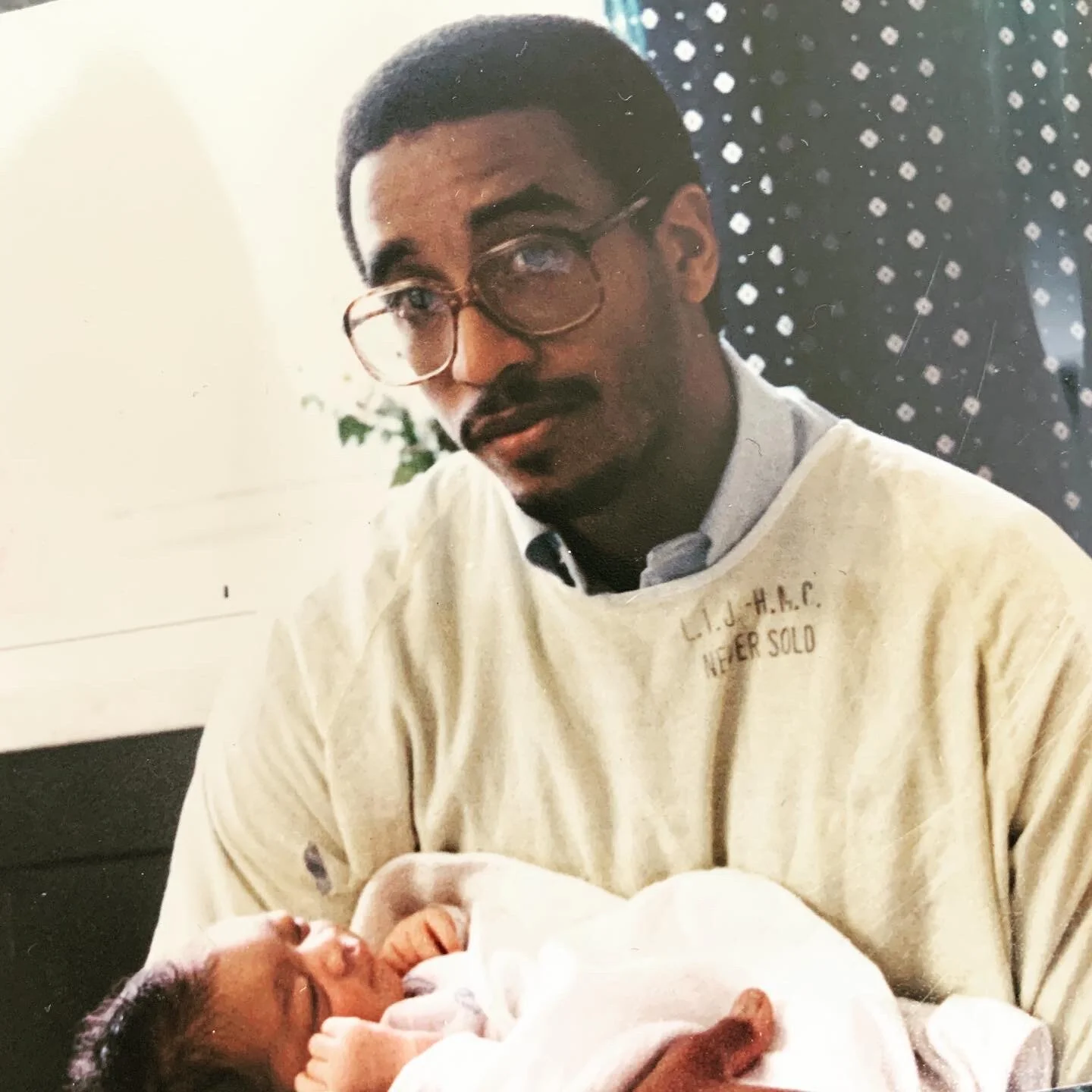

When I asked my father and my uncles and aunt about my grandfather they didn’t describe him as warm. They said he was intimidatingly strong, had a booming voice and was always working. As his first granddaughter, my experience was different. By the time I arrived he was retired, he had returned to Anguilla and was swimming in the ocean every day. I can count on my hand the amount of times I saw him wearing a shirt. The distance his children felt because of his constant work was something I pre-empted immediately, according to my grandfather. I would grab onto his long white beard and refuse to let go. They would have to wait until I fell asleep to pry my little fingers open. I had made my claim. But to his own children he was a larger-than-life figure, a hard worker and a strict disciplinarian. “Those who do not hear will feel,” he would say before the spankings he gave which were his children’s only vivid descriptions of touch. It wasn’t until they were adults that they learned about another manifestation of his warmth.

As my father, uncles and aunt grew up and did their own work in the New Jersey and the NY Tri-state area they would often get the question. Gumbs? Are you related to Jeremiah Gumbs? When they said yes the stories would come pouring out. Grown black folks and immigrants of many ethnicities would have tears in their eyes. The stories would come gushing out about how if it was not for Jeremiah Gumbs they would not have made it during this or that winter. Their parents didn’t have the money for coal or heat and he still made sure they were warm through the winter. People would ask sincerely if there was anything they could do for them, the children of Jeremiah Gumbs, to show their gratitude. Their vulnerable opens hearts, a form of warmth moving across the years. Their memories of my grandfather (before he grew the white beard that would make me think he was the prototype for Santa Claus) actually giving them coal, the best possible gift for a difficult Christmas.

I wonder if that warmth could travel backwards to the consciousness of my father and his siblings to recontextualize the absence they felt, because their father was always working. Even on his birthday. My father said that for his father, a good day, was a day that he could work. Work itself was the gift. I have had to balance this tendency within myself, a coldness borne from how much more in control of my emotions I feel when I am living in the context of work. Sometimes I avoid the messiness of actual relationships by imagining that work is the entire world. My grandfather loved his work. He loved the fact that he was able to own his own business and work for himself. There is also evidence that although his business made many things possible in the lives of his family members and for his home communities in Anguilla and New Jersey that he was also not a good businessman. Because he could not, in the face of winter agree that the money a family had was the determining factor in whether they would be warm. He felt that he was the determining factor because he had access to the apparatus to keep them warm and so he made it work. He made many investments motivated not by their ability to provide returns but because of his belief in the community and family members who asked for his support. Many times he felt betrayed by people he had supported who didn’t feel accountable to him after the fact. I have read his correspondence with my grandmother, she would write justifiably stressed out about their financial situation, and he would reply with faith that eventually everything would work out.

Today, on my grandfather’s birthday I am thinking about warmth and what it means to us. I am thinking about how most of us are dependent not on the neighborhood man who is provider of coal, but on a power grid that will perpetuate existing privileges and never have to look us in the eye. We are disconnected from warmth, not only because of the unsustainable infrastructure we pay into, but because we all repeat and believe that we are not the determining factor. We depend on systems supposedly designed to support human life where human life is not the determining factor. I’m a writer. And so here I am working on my grandfather’s birthday. Watching the ice storm out my window, wondering when the power lines will go down. The power company has already emailed to say not to contact them, but to sign up for text alerts if I want to know how long it will take for them to restore power based on priorities I can already predict.

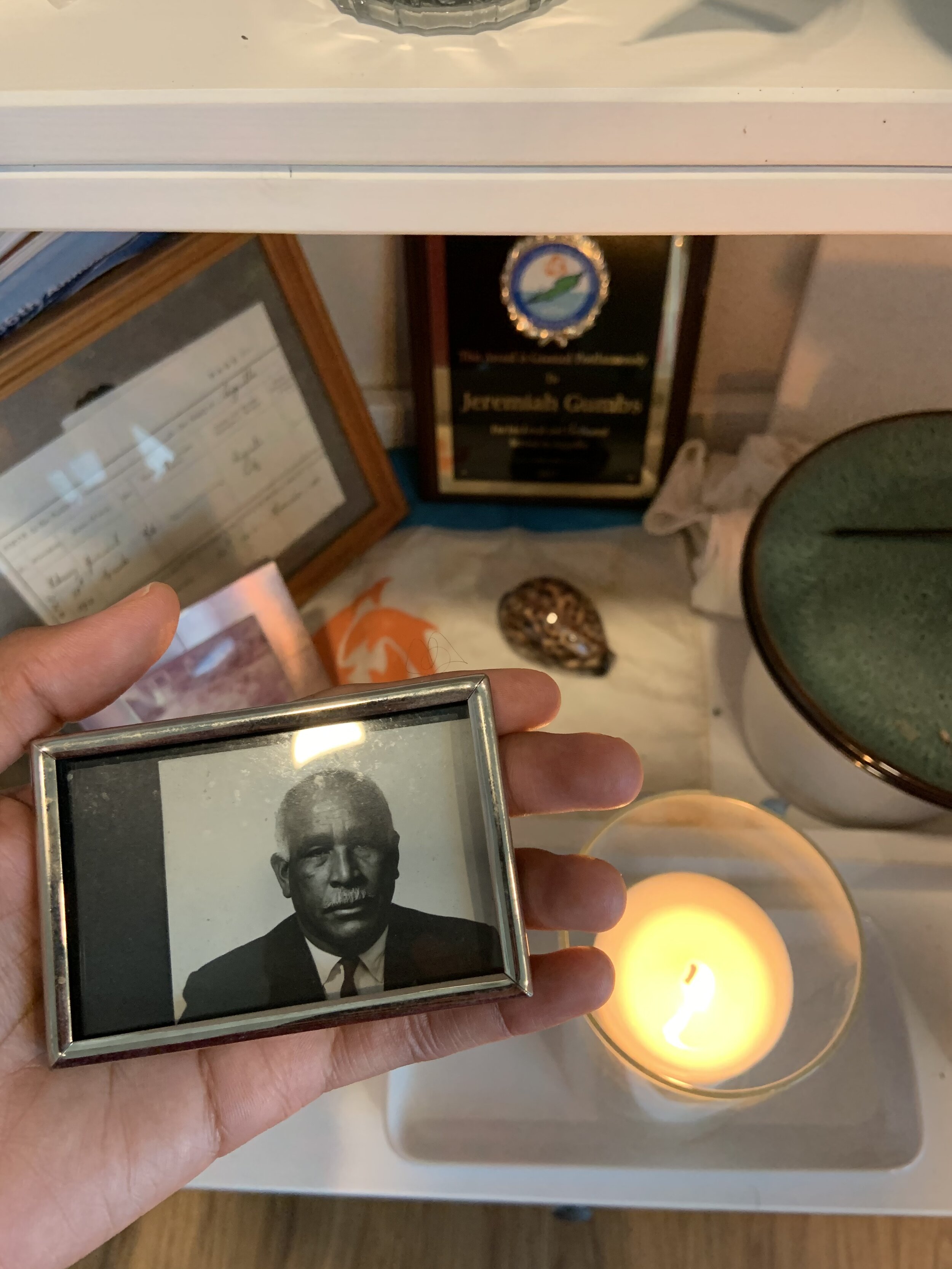

I lit a candle on my ancestor altar this morning for my grandfather’s birthday. I want to cultivate the faith to believe that I could be the determining factor, that we together could determine that nobody is left in the cold not today on my grandfather’s birthday and not any day. I turn to blankets and the body-heat of my partner. I turn to memories and warm thoughts. But I also turn to this work. May it matter that I wrote this. May this be the work that outlives profit. May it be a part of how we learn what warmth actually is. May it support us when we feel bereft. May it light the way as we become determined enough to face our responsibility for everyone’s survival. And in the meantime, I am holding onto you determined as ever with the knowing and strengthening grip of these, my hands.

P.S. My every day writing practice shapes my days into vessels for generations of love. If you want support with your own daily creative practice, I’d love to be part of your journey. This is the Stardust and Salt Daily Creative Practice Intensive.